The growing rivalry between the United States and China in the production of rare earths elements (REEs) is playing out on distant African grounds where there are plenty of resources. Africa has turned into a strategic battlefield as both superpowers want to establish the supply chains of the critical minerals. It is a story that explores the way nations such as Democratic Republic of Congo, Malawi and South Africa are balancing geopolitical forces as they seek to capitalize on the increasing world demand of the rare earths.

Africa is again at the epicentre of a great-power competition over rare-earth elements (REEs) which are essential to electric cars, modern smartphones, wind turbines and sophisticated missiles, in this instance, a flashback to colonial-era scramble for Africa. The U.S and China are rushing into the mineral-rich geographies of Africa staking claims, making deals and escalating the threat of economic sovereignty of Africa.

With growing friction between the US and China over who will dominate technological innovation in the world, the conflict appears to take place not only in Silicon Valley or Beijing, but more importantly, in Africa. The big African continent, which is endowed with large yet untapped reserves of rare earth element (REE), has been locked in an arms race of major powers, all keen to ensure their future in a low-carbon and high-tech world.

One of such minerals is a set of 17 rare earths which are used in electric vehicles (EVs), wind turbines, smartphones, and military systems. However, Beijing has a near-monopoly (over 85 percent of the world processing), which alarmed the decision-makers in Washington and Brussels. The fact that recently Beijing cut its exports of REE magnets by 74% and exports to the U.S. fell by 93% percent, compared to the previous year, speaks volumes about geopolitical weaponization of these minerals. In the meantime, Western countries and industries continue to look at Africa as a source of raw materials as well as an opportunity of developing new alliances to transform global supply chains.

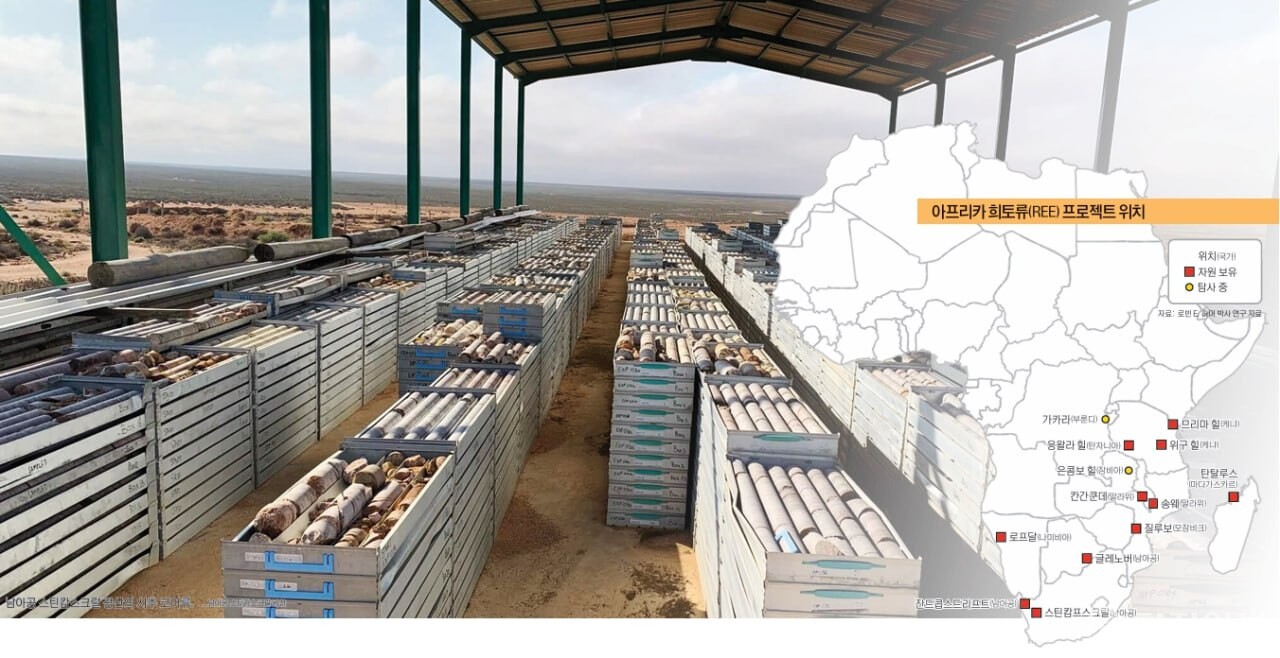

The report of a large African Development Bank (AfDB) survey holds that Africa has an excess of 4 million tonnes of rare earth oxides, with deposits as high as those in the world, including Lofdal in Namibia, and Steenkampskraal in South Africa. Other major initiatives are Gakara in Burundi (then already exporting concentrates), Songwe and Kangankunde in Malawi, and Mrima Hill in Kenya. However, majority of these projects are in the initial phases of value chain- raw extraction with any little beneficiation locally.

With the geopolitical chessboard changing in the 21 st century, rare-earth elements (REEs) have emerged on the axis of the growing conflict between the United States and China. Although these strategic minerals are vital in a smartphone, electric cars, renewable energy technologies, and advanced weapons systems, it is Africa with its unexplored reserves of such mineral deposits that has become the key battlefield where up to 20 countries fight to control the vital resources. As the two superpowers hustle to establish long-term supply chains, the continent has been thrown into a high-paced tug of war that may reform its economic direction and geopolitical affiliations.

China now has control over the global rare earth market with the U.S. Geological Survey estimating that it controls close to 70 percent of the world production and more than 85 percent of the processing capacity, as reported by the recent Wall Street journal write-up. Beijing has employed such dominance as a geopolitical leverage in the past and the symptoms of tightened grip are emerging. In May 2025, China reduced rare-earth magnets exports by 74 percent annually, and deliveries to the U.S. declined by 93 percent, as an apparent sign of the willingness to use its supply chain dominance as a weapon. With Washington getting more and more paranoid of this stranglehold, the U.S. policy makers and partners are looking to Africa to hedge and gain interaction of alternative sources.

A number of African countries have become major actors of this drama. Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is already vital due to its cobalt production; on top of that, other rare earths are also found in great reserves in DRC. Under the frameworks of Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Chinese firms have deep-rooted themselves in the DRC mining industry by accepting long-life leases and infrastructure-minerals swaps. Informed sources have reported that as evident in consultations currently underway between DRC officials and the U.S., the latter is ready to offer its immature chinaman security and development packages in exchange of its monopoly over Chinese mineral deposits through Modern Diplomacy.

In addition to the DRC, there is greater interest in Malawi, Namibia and Kenya. The Mrima Hill of Kenya contains the REE deposits and they also contain joint ventures between the Australian and Kenyan interests that have increasing U.S. participation. Malawi and Burundi hold discussions with the U.S. department of defense, as they want to obtain REEs, which are second hand supplied, directly on the continent. In the meantime, Namibia and Zimbabwe are also trying to make the shift towards becoming processors of value-added products, imposed the ban on exporting raw materials of lithium and rare earths. Such actions though attracting more national gain are also transforming the way in which the changing resource nationalism would necessitate the global powers to interact with Africa.

But in chasing the rare earths of Africa, there are some troublesome issues on sovereignty, sustainability and strategic independence. Critics have denounced a new neo-colonialism, with Chinese and Western firms dividing up the African mineral rights so that the local people are left as poor populations with destroyed ecosystems. In other countries such as Zambia and Madagascar, the environment is facing greater pressure as poorly controlled mining activities have led to pollution and evictions. To avert elite capture and corruption to erode the development merits of mining booms, Transparency International and local nongovernmental organizations have proposed stronger governance structure.

With these dynamics, we are seeing an increase by African leaders in terms of agency. The export control policy of Zimbabwe and Namibia is indicative of their increasing interest to make the step above rather than become suppliers of raw materials. Cross-border value chains and regional beneficiation hubs that amplify the bargaining power could be facilitated by the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), in case it is exploited as an incentive. Such scholars as Yonas Yizezew of Horn Review opine that, “Africa might become the strategic alternative to Chinese mineral dominance, provided that it will not be engaged on a basis of unrecognized African agency and will not serve as a source of raw materials.” The continent is projected to have 30 percent of the world critical mineral reserves fact that puts it in a position of advantage, as long as it is used skillfully.

Even with the increased concern, there is uneven-ness in the manner with which the U.S. and China are conducting their affairs in Africa. The Chinese investments are long-term, infrastructure-intensive and are usually associated with state loaning. The U.S approach has been, in comparison, smaller in scope and proportion. A 2025 Reuters report states that, conversely, though the U.S. and G7 have promised a critical minerals strategy, real investment into African extraction and processing is so far low, at less than $300 million, compared with an estimated $8-10 billion invested by China over the last five years. Moreover, there are also diplomatic lapses; the potential expansion of cooperation is adversely affected by several West African countries complaining about the U.S. visa ban and the low level of high-level contacts.

With the rare-earth race gaining pace, the next few years will tell how Africa will be a pawn in the global tech cold war or a central player in plotting its industrial destiny. The threats are not theoretical; it is ecological degradation, economic subordination, and strategic sidelining. The opportunities are also there, so to speak: by coordinating the policy, making their governance more transparent and their partnerships more strategic, the African countries would be able to redesign their place in the global economy, with rare earths not as a bargaining chip but as a means of sustainable development.

What the policy architects in Africa want to turn around is this unbalanced system of extraction, extraction, export, and importation of the end products. According to the African Natural Resources Centre (ANRC) of the AfDB, the only solution to it is to forcefully find their way in the REE supply chain vertically, so as to enable them to seize the entire supply chain, which consists of three phases: (1) upstream mining and beneficiation, (2) intermediate processing and separation, and (3) downstream manufacturing of magnets and high-tech components. Nevertheless, the research findings indicate that although African countries consume technologies using REE in wind machine,Electric cars (EV), and electronics, none of them has been able to produce such capabilities in phase 3.

The economic reason is obvious. It is estimated that Africa minerals will also play a major role in providing the global low carbon transformation. The demand of some of the rare earth metals such as neodymium, praseodymium and dysprosium would increase more than 650 percent in a world full of electric vehicles. As EV sales in the world are projected to increase by 60 times to 32 million between 2019 and 2030, and magnet demand is expected to grow by 30 percent due to the wind power, African governments have a unique situation at hand-should they be able to capture a larger part of the value locally.

However, there is a number of limitations which prevent any change. Majority of countries in Africa do not have the technical base, regulations, and investment environment able to sustain sophisticated processing and manufacturing of minerals. Besides, the lack of cross-border value chain organization is obstructed by the uncoordinated whole in the regional integration. Regional processing hubs with, possible, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) have been proposed in the ANRC report, which would permit smaller countries to unite resources to attract greater industrial investment. Worldwide competitors are paying attention.

The U.S. via its Defense Production Act and alliances such as Minerals Security Partnership (MSP) is set to invest along African projects in order to minimize its reliance on China. Rivalries to get hold of supplies in Africa have also come up with Australia, Canada, Japan and the EU. These initiatives are however prone to reinforcing the same of extractive status quo unless African countries exercise more control over the local content, transfer of technology, and environmental protection.

The scholars fear a fresh scramble of Africa in green energy euphemisms. According to Dr. Emmanuel Pinto Moreira, the ANRC, the industrialization of Africa is not going to take place by chance. It demands concerted plans, mutually beneficial partnerships and value chain capacity building.” The research advises governments to enhanced geological mapping, provide improved incentives to value-added investment and follow the industrial leapfrogging catches in the East Asian so-called tiger economies.

Further, the domestic market synergies that are to be tapped are still available. In Uganda, as an example, when Ionic Rare Earth sends its REE concentrates overseas, Kiira Motors, the first electric vehicle maker in the country, imports magnets and batteries that are made out of the same minerals that it extracts on the ground. Given an appropriate policy framework, these connections can be transformed into national or regional schemes of REE-to-EV industry.

It is a high stake game. Unless Africa is active not only in exports, there is a danger of losing an opportunity of transformation. However, by being smart with its mineral wealth, building local industry, and partnering with the cleanest hands across the world, it could turn itself into the heart of the global energy transition, and a powerhouse on its own in a multilateral rare earth future.